Hell Albertine Rift Herbaria Network (ARHN)

About

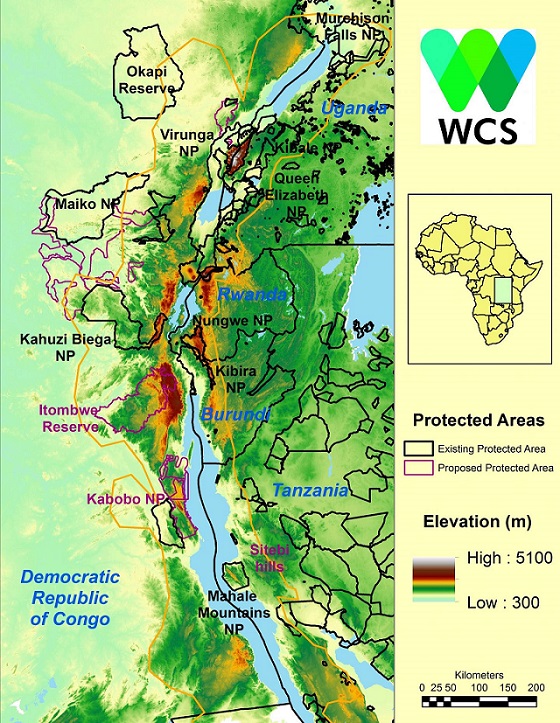

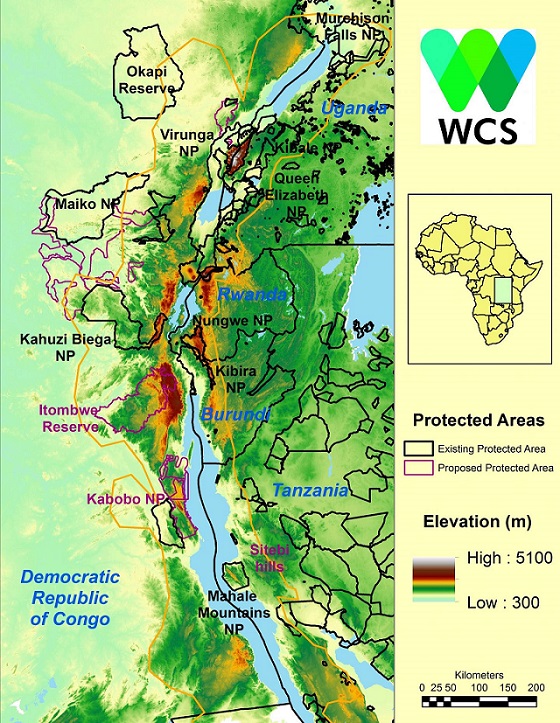

The Albertine Rift (AR) is the western branch of the East African Rift, covering parts of Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania. It extends from the northern end of Lake Albert to the southern end of Lake Tanganyika. The geographical term includes the valley and the surrounding mountains.

By many measures of biodiversity of the Albertine Rift Region stands out as being globally important. The Albertine Rift or Africa’s Western Rift Valley is one of the most biodiverse regions of the African continent. With more than half of Africa’s birds, 40% of Africa’s mammals and about 20% of its amphibians and plants, it contains more vertebrate species than anywhere else on the continent. It also conserves more threatened and endemic species than any other region of Africa, and as a result is a Biodiversity Hotspot, a Global 200 Ecoregion and an Endemic Bird Area. Human population density in the Albertine Rift is also high with over 1000 people per square kilometer in some areas of the Rift, with some of the poorest people on the continent.

Within the Albertine Rift there are numerous underdevloped and undigitized herbaria collections. Although these collections well-document the flora of the region, they are underutilized and inaccessible via the Internet due to a lack of both specimen digitization technologies and expertise in the host countries.

This project will leverage the experiences gained from the completion of related herbaria specimen digitization projects and extend this data mobilization model to 5 regional herbaria including specimen collections in Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Rwanda. The focus is on accelerating the discovery of undigitized regional herbaria specimen data the alignment of the Africa Regional Strategy with the GBIF Strategic Plan and Work Programme. This will be accomplished through a series of training workshops on specimen digitization, data portal implementation, and data publishing including data harvesting through GBIF partnership.

Significant goals for the project would be to:

1) Enable national- or regional-level integration and curation of herbaria datasets into a centralized data portal including data harvest through GBIF partnership,

2) Collaborate with other herbaria for the repatriation of plant specimen data,

3) Enhance herbaria data records to reflect national or institutional administrative units and national species checklists,

4) Provide tools that meet the requirements of national or regional researchers, policymakers and the general public,

5) Provide opportunity for taxonomic and geographic gap analysis in the available data.

The classification systems used in this Flora will reflect current understanding of phylogenetic relationships of the plant groups. The APG IV system will be adopted for angiosperms, and up-to-date phylogenetic systems of gymnosperms, ferns and lycophytes will also be reflected in treating these groups.

Literature Cited

Allen W. H. 1993. The rise of the botanical database: Computerized information offers increased efficiency, access to unpublished records, and new ways of asking questions. BioScience 43: 274–279.

Chapman A. D. 2005. Uses of primary species-occurrence data. Report for the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, Copenhagen, Denmark. Website http://www.niobioinformatics.in/books

iDigBio. 2013. Mobilizing Small Herbaria Workshop. 10–11 December 2013. Website https://www.idigbio.org/content/mobilizing-small-herbaria-workshop [accessed 13 December 2018].

Lane M. A. 1996. Roles of natural history collections. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 83: 536–545.

Myers, N., R.A. Mittermier, C. G. Mittermier, G.A.B.da Fonseca, and J. Kent. 2000. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature. 40:853-858.

Nelson G., Sweeney P., Wallace L. E., Rabeler R. K., Allard D., Brown H., Carter J. R., et al. 2015. Digitization workflows for flat sheets and packets of plants, algae, and fungi. Applications in Plant Sciences 3: 1500065.

Network Integrated Biocollections Alliance (NIBA). 2010. A strategic plan for establishing a Network Integrated Biocollections Alliance. Website https://digbiocol.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/niba_brochure.pdf [accessed 13 September 2016].

Olson, D. and E. Dinerstein. 1998. The Global 200. A representation approach to conserving the Earth’s most biologically valuable ecoregions. Conservation Biology 12(3):502-515.

Owen R. D. 1990. Database computerization and consortium development for vertebrate collections: A collection management perspective. In E. M. Herholdt , Natural history collections: Their management and value, 105–116. Transvaal Museum Special Publication No. 11. Transvaal Museum, Pretoria, South Africa.

Schmull M., Heinrichs J., Baier R., Ullrich D., Wagenitz G., Groth H., Hourticolon S., Gradstein S. R. 2005. The type database at Gottingen (GOET): A virtual herbarium online. Taxon 54: 251–254.

Stattersfield, A.J., M. Crosby, M.J. Long, D.C. Wegge. 1998. Endemic Bird Areas of the World. Priorities for biodiversity conservation. BirdLife International, Cambridge, U.K.

Thomas, M.B. 2018. Biological Specimen Collections of Bhutan: Biological Specimens of Bhutan. Website. http://www.bhutanbiodiversity.net/ [accessed 13 December 2018].

WWF/IUCN. 1995. Centres of plant diversity: A guide and strategy for their conservation. Vol 2. Asia, Australasia and the Pacific. World Conservation Union Publications Unit, Cambridge, UK.

About

The Albertine Rift (AR) is the western branch of the East African Rift, covering parts of Uganda, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania. It extends from the northern end of Lake Albert to the southern end of Lake Tanganyika. The geographical term includes the valley and the surrounding mountains.

By many measures of biodiversity of the Albertine Rift Region stands out as being globally important. The Albertine Rift or Africa’s Western Rift Valley is one of the most biodiverse regions of the African continent. With more than half of Africa’s birds, 40% of Africa’s mammals and about 20% of its amphibians and plants, it contains more vertebrate species than anywhere else on the continent. It also conserves more threatened and endemic species than any other region of Africa, and as a result is a Biodiversity Hotspot, a Global 200 Ecoregion and an Endemic Bird Area. Human population density in the Albertine Rift is also high with over 1000 people per square kilometer in some areas of the Rift, with some of the poorest people on the continent.

Within the Albertine Rift there are numerous underdevloped and undigitized herbaria collections. Although these collections well-document the flora of the region, they are underutilized and inaccessible via the Internet due to a lack of both specimen digitization technologies and expertise in the host countries.

This project will leverage the experiences gained from the completion of related herbaria specimen digitization projects and extend this data mobilization model to 5 regional herbaria including specimen collections in Burundi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Rwanda. The focus is on accelerating the discovery of undigitized regional herbaria specimen data the alignment of the Africa Regional Strategy with the GBIF Strategic Plan and Work Programme. This will be accomplished through a series of training workshops on specimen digitization, data portal implementation, and data publishing including data harvesting through GBIF partnership.

Significant goals for the project would be to:

1) Enable national- or regional-level integration and curation of herbaria datasets into a centralized data portal including data harvest through GBIF partnership,

2) Collaborate with other herbaria for the repatriation of plant specimen data,

3) Enhance herbaria data records to reflect national or institutional administrative units and national species checklists,

4) Provide tools that meet the requirements of national or regional researchers, policymakers and the general public,

5) Provide opportunity for taxonomic and geographic gap analysis in the available data.

The classification systems used in this Flora will reflect current understanding of phylogenetic relationships of the plant groups. The APG IV system will be adopted for angiosperms, and up-to-date phylogenetic systems of gymnosperms, ferns and lycophytes will also be reflected in treating these groups.

Literature Cited

Allen W. H. 1993. The rise of the botanical database: Computerized information offers increased efficiency, access to unpublished records, and new ways of asking questions. BioScience 43: 274–279.

Chapman A. D. 2005. Uses of primary species-occurrence data. Report for the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, Copenhagen, Denmark. Website http://www.niobioinformatics.in/books

iDigBio. 2013. Mobilizing Small Herbaria Workshop. 10–11 December 2013. Website https://www.idigbio.org/content/mobilizing-small-herbaria-workshop [accessed 13 December 2018].

Lane M. A. 1996. Roles of natural history collections. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 83: 536–545.

Myers, N., R.A. Mittermier, C. G. Mittermier, G.A.B.da Fonseca, and J. Kent. 2000. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature. 40:853-858.

Nelson G., Sweeney P., Wallace L. E., Rabeler R. K., Allard D., Brown H., Carter J. R., et al. 2015. Digitization workflows for flat sheets and packets of plants, algae, and fungi. Applications in Plant Sciences 3: 1500065.

Network Integrated Biocollections Alliance (NIBA). 2010. A strategic plan for establishing a Network Integrated Biocollections Alliance. Website https://digbiocol.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/niba_brochure.pdf [accessed 13 September 2016].

Olson, D. and E. Dinerstein. 1998. The Global 200. A representation approach to conserving the Earth’s most biologically valuable ecoregions. Conservation Biology 12(3):502-515.

Owen R. D. 1990. Database computerization and consortium development for vertebrate collections: A collection management perspective. In E. M. Herholdt , Natural history collections: Their management and value, 105–116. Transvaal Museum Special Publication No. 11. Transvaal Museum, Pretoria, South Africa.

Schmull M., Heinrichs J., Baier R., Ullrich D., Wagenitz G., Groth H., Hourticolon S., Gradstein S. R. 2005. The type database at Gottingen (GOET): A virtual herbarium online. Taxon 54: 251–254.

Stattersfield, A.J., M. Crosby, M.J. Long, D.C. Wegge. 1998. Endemic Bird Areas of the World. Priorities for biodiversity conservation. BirdLife International, Cambridge, U.K.

Thomas, M.B. 2018. Biological Specimen Collections of Bhutan: Biological Specimens of Bhutan. Website. http://www.bhutanbiodiversity.net/ [accessed 13 December 2018].

WWF/IUCN. 1995. Centres of plant diversity: A guide and strategy for their conservation. Vol 2. Asia, Australasia and the Pacific. World Conservation Union Publications Unit, Cambridge, UK.

Copyright (c)2020. Data portal development has been supported through the cooperation of Biocultural Diversity International and the National Herbarium of Rwanda (NHR)

at the Center of Excellence in Biodiversity and Natural Resources Management (CoEB).

We are currently actively seeking additional funding for this project.

Powered by Symbiota software with site management and data curation support by Michael B. Thomas, PhD. Usage Policy.